About a week ago, I attended an all-hands meeting at a client of mine. It was generally meant for catching up with other team members—the company is pretty small, and it’s a good way to feel connected as a remote workforce.

The CEO had just attended a seminar and wanted to share some of the insights he gained from it: it was mostly about things that more or less existed implicitly in the company, but had never been spelled out, and trying to create a vocabulary around them seemed like a useful exercise.

A lot of the insights were about leadership structures—leader-leader instead of leader-follower and other things that sound good, but are hard to actually pull of—, but one of his take-aways in particular stood out to me. The idea seemed somewhat embryonic, and it didn’t have a good name yet. In this post I want to give it a name—contextual leadership—, and try to define it, in an effort to both start the discussion internally and to share it with the outside world.

Contextual Leadership: my first buzzword

Before we start actually talking about the idea I want to address something about it: the name. It sounds vaguely business-y and hollow to me, like something you’ll read about in a mediocre book about working in middle management.

I’m not good at naming things—I frequently use one letter variable names and the names of things are the weakpoints of all my APIs. As such, I present what I have as a concept foremost; the name is secondary. I do think it is important, because I subscribe to the notion that to know the name of a thing is to have power over it.

With all of this cruft out of the way, let’s move on.

Hierarchies and other blunders

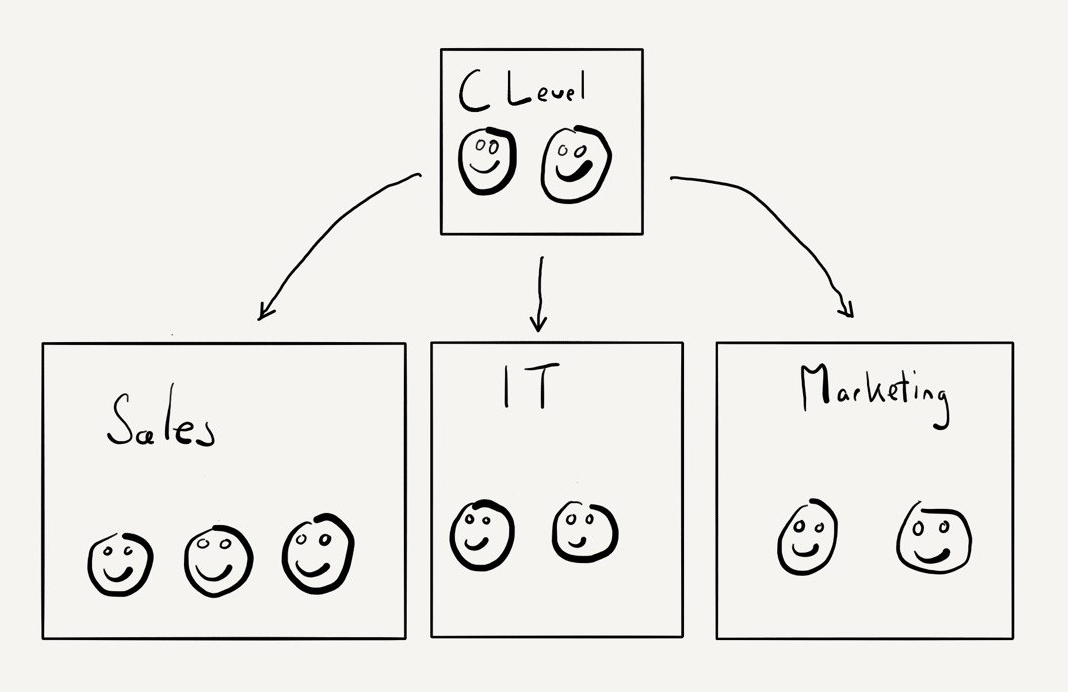

Often, when we talk about leadership, we talk about hierarchies. In a small company, a hierarchy might look like the diagram in Figure 1. In bigger companies, it will be more complicated, too complicated for me to want to draw it.

This is great if you want to know the general structure of an organization, but it doesn’t make sense when you need to know how a specific process works. Let me give an example that I suspect my readers can empathize with most easily: say a piece of infrastructure—let’s take the company issue tracker—needs to be migrated from an old system that no longer fulfills the company’s needs to a new, promising system. It’s spearheaded by a member of the IT team who sets up the system. They need support by their team firstly, but eventually they will also need to talk to the other departments to schedule onboarding workshops and the like.

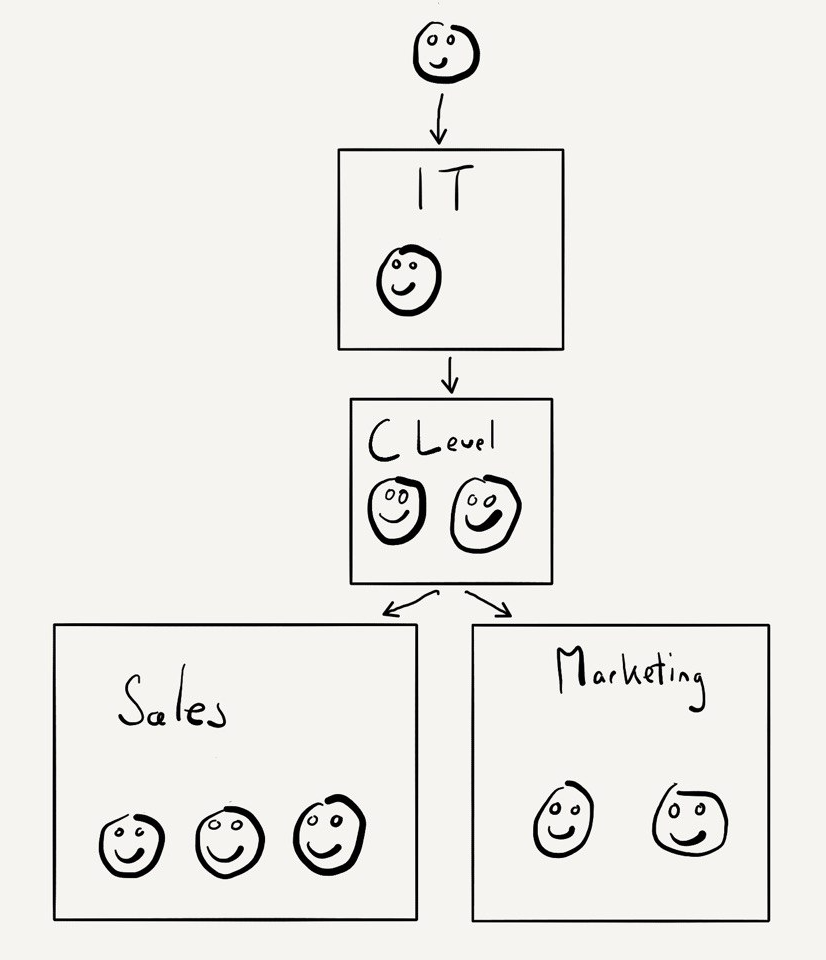

Will the diagram above do a good job of illustrating the organizational structure of that project? I would argue that it won’t. Something like the diagram in Figure 2 might do a better job.

Note that only two arrows have been flipped and the diagram reordered. This diagram doesn‘t cover the flow of power within the organization, but it does capture responsibilities, support channels and process:

- The team member on top is responsible for the project.

- If that team member needs assistance, they would first ask their team, and then escalate within the organization.

- The project would be worked on by that person, vetted by their team, and then rolled out in the organization—maybe not top-down, but that’s a decision that needs to be made on a case-by-case basis anyway.

This diagram is not helpful outside this particular process, which is why I call it “contextual”, and it’s not about hierarchies, but it is about responsibilites and information flow, which is why I call it “leadership”.

So this is about diagrams, yeah?

All of this build-up just for a couple of diagrams? Well, yes and no. I don’t think the diagrams themselves are important—as you might have been able to deduce from my drawings I’m not a very visual thinker. What’s important is the idea of thinking about leadership as something contextual and flowing rather than about something static. Sure, hierarchies are important for an organization of a certain size1, but they don’t capture the essence of leadership, at least not always.

If leadership were static, individual autonomy and motivation would be taken away, and the only way to have any say about aynthing at all would be climbing the ladder of hierarchy rung by rung, and who would want to work in a company like that?

Jokes aside, if you want your team to show initiative, you have to give them autonomy. Thinking of leadership as contextual and giving it up every once in a while might be a good way to do that.

Fin

I don’t think I have anything more to say about that. As with many ideas about leadership you could probably write a book about this idea, with case studies and detailed instructions on how to implement it in your organization. The essence of the idea is rather easy to grasp, though, and leaving this a sketch, an idea, will force you to think about whether it would make sense to implement this in your organization(s), and if so, how to go about it, and I believe that makes most sense.

As always, if you want to bounce ideas off of me, or tell me that I should stop writing about business stuff and write about Lisp macros again, you know how to reach me!

Footnotes

1. The path less travelled, organization without hierarchy, is more exciting to me, but it’s sadly also woefully underpracticed.